I am lazy. When I started to become a classically trained painter, I soon realized that I had to invest a lot of time in the paintings I wanted to produce. Hours became days. Days turned into weeks. And weeks turned into months before I could finish a single painting. It was the time when I became interested in programming. I could tell a computer what, how, and where to paint, and it did it. Much faster than I could have done it in my painterly style. Today I work with artificial intelligence and teach it to paint: I’m painting with AI. Initially using art historical milestones that revolutionized and/or significantly changed the means of artistic production. Think of the Industrial Revolution, the Russian avant-garde, the Bauhaus, and Warhol’s Factory.

However, I soon realized that the model was far too small to produce artistically exciting results. Then came Corona. On the one hand, the lockdowns gave me the opportunity to invest more time in the development of my AI. On the other hand, many art institutions digitized their collections to make them available to visitors during the lockdowns. This was a godsend for me, as it gave me machine-readable access to a large amount of professionally curated art. A bot was quickly written which fed the artworks into a database. And after a short time, the model was up to the stately size of 250,000 artworks from classical to contemporary modernity.

Since I started working on AI, I realized that patience eats laziness for breakfast. Because hours turned into days. Days became weeks. Weeks became months and months became years until I could produce an image.

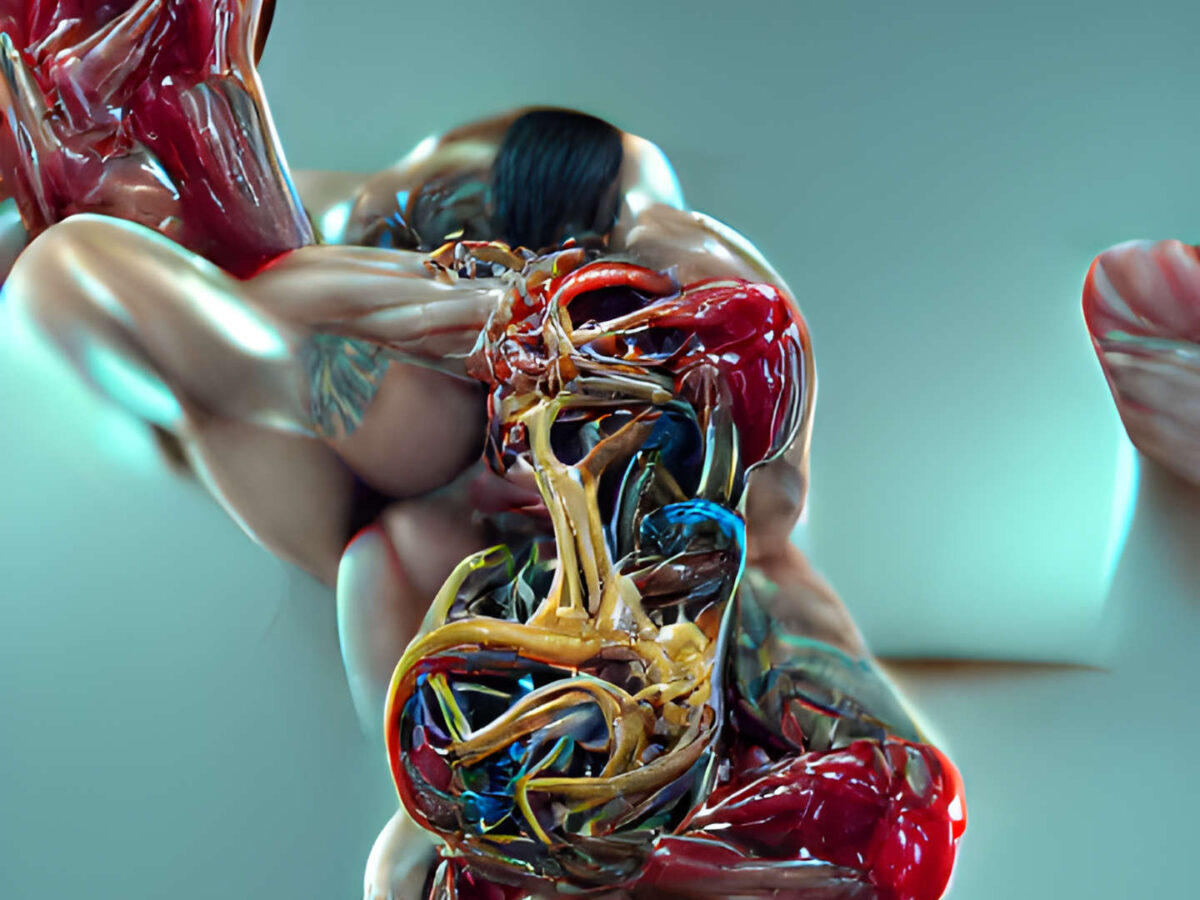

Painting with AI: I believe it’s dark inside my closet when I close the door.

After growing the painting AI model to a volume of roughly 250K, it started to replicate composition, ductus, and light & color theory – the basics of painting I learned during my studies at university. Ever since I started to work with AI I was interested in the complicated relationship between the seemingly “smart” machine and us humans as its user.

Which interaction possibilities and interfaces open up? Which senses and cognition tools do people have to understand a ‘black box’, like the products of an AI? And is there a form of machine vision – aesthetic artifacts – which on the one hand are created by the correspondence between two machines and on the other hand may not be recognized as such by people who do not have the corresponding sensors.

My research of the implications of painting with AI led to a deeper exploration of philosophy, machine ethics, and art theory. In the process, I encountered the art historical underpinnings through Rosalind Krauss’s idea of the ‘photographic object’ (Baker, 2005), which sent me on a journey of discovery across the centuries. Throughout the history of photography, I discovered the beginning of a current that I could follow into contemporary modernism. This is the idea of considering the artistic production process in the course of an indexical-technological transformation, which finds a contemporary extension through AI.

The art of the machine

There are many examples of art produced by machines, and evidence that thinkers have thought about art machines and machine-made works of art can be traced back to the 1st century BC. The development of photography shows that not only analog art machines can be located within an art theoretical frame of reference, but also abstract and digital approaches in which the artistic reference object and its production are subject to a programmatic set of rules.

The premise for many critical discourses in and about art is, on the one hand, the relevance and central role of the artist, and, on the other hand, the representation of their subjective reality on the basis of partially nebulous parameters, such as the amount of work, the meaning of the creative process, intention, and biographical narratives. When considering AI-generated art, the idea of subjecting a work of art to traditional, inherently human structures in analysis and evaluation turns out to be not unproblematic. […]

For, as a converse conclusion, one would have to assume that the primacy of the gaze, i.e. the sum of sensory data available to human recipients when viewing a work of art, establishes the aesthetic perception of objects, and at the same time this ability is denied to non-human entities. “I cannot imagine what it is like to be dead since to imagine it means we are still alive” says Quentin Meillassoux, when he clearly grants objects a raison d’être outside of human cognitive structures. The apparent inability of objects to withdraw into a radical autonomy and contingency, accessible only in a roundabout way and only in parts, nullifies the possibility that machine gaze can be an experience that consistently refuses to enter the human spectrum of experience.

This inability would further mean that especially AI-based artworks remain closed to many artistic fields of meaning and media and that the prominence of the machine can be understood exclusively as a curious primitivism, instead of being understood as an independent, intra-machine transformation process of a photographic apparatus. […]

However, this is accompanied by a shift in the conceptualization of the work of art itself, since now we no longer speak of a media-specific object with auratic properties, but the act of programming itself can be understood as a performative, creative act, and the final product is basically a form of documentation of the application of a set of rules over time.

Thus, there is no longer a need to examine the quality of reproduction as a source of originality. For through this deconstruction of artistic practice, it is possible to fix the question of originality through an act with creative intent not on the material or the representational nature of the artwork, but on the body of the artist. Should the discourse continue to be oriented towards the object, i.e. the question of creative intention, it seems to become necessary to make a clear characterization of the different forms of ‘agency’ of AI.

As the field is particularly biased by dystopian Hollywood myths, such as Skynet and Terminators, sci-fi narratives should be identified and viewers should refrain from baseless speculations that AI will be more than just a glorified calculator in the foreseeable future. Mark Riedl sums up this fact very aptly :

“Neural networks are kind of in the imitation mode, you can pipe in the works of the classics and they’ll learn patterns, but they need to learn creative intent somewhere.“

Mark Riedl (Simonite, 2016)

Consequently, the central question is not whether machines can produce art, but how this art, which is already created on an ongoing basis, finds its way into the Kraussian ghetto of art? What gaze must be established so that an object with artistic properties, which has been produced by AI, can be seen not as a reproduction, but as an independent, photographic object?